This guest post by Susan Bennett-Armistead, author of our

My World informational texts

, is the first in an ongoing series in which she discusses informational text and its benefits and uses. Check back regularly to catch her next post!

This guest post by Susan Bennett-Armistead, author of our

My World informational texts

, is the first in an ongoing series in which she discusses informational text and its benefits and uses. Check back regularly to catch her next post!

Building World Knowledge in Early Childhood Settings

A couple of years ago, I was invited to a preschool classroom to do a read aloud.

I planned to read

To Market, To Market

, so I asked the children to think about a time they went to the grocery store. To my surprise, of the twelve children in the class,

four of them told me they had never been in a grocery store

. You can imagine that my read-aloud choice didn’t work so well with people that had no idea what was supposed to go on in a grocery store. They didn’t get the visual jokes included by the illustrator, and they had no way of knowing how to answer any of my carefully prepared comprehension questions.

That experience helped me reflect on a chat that I’d had with an exasperated colleague years ago when she announced, “I’ve got a kid with no prior knowledge! How am I supposed to activate that?!” It was true. He had very little prior knowledge about picnics and playing in the park. He knew an awful lot about staying safe in a dangerous city, though. When we talk about activating children’s prior knowledge, we usually mean about school-related topics.

Some children have the advantage of lots of experiences that they can draw upon while others may have narrower or less school-relevant experiences. Building world knowledge can help level that playing field.

That experience helped me reflect on a chat that I’d had with an exasperated colleague years ago when she announced, “I’ve got a kid with no prior knowledge! How am I supposed to activate that?!” It was true. He had very little prior knowledge about picnics and playing in the park. He knew an awful lot about staying safe in a dangerous city, though. When we talk about activating children’s prior knowledge, we usually mean about school-related topics.

Some children have the advantage of lots of experiences that they can draw upon while others may have narrower or less school-relevant experiences. Building world knowledge can help level that playing field.

So what is world knowledge, and why should we care? For our purposes, world knowledge is awareness of the world around us, both the natural world and the social world . When we talk about building world knowledge, we’re addressing the fact that the more we know, the more we can comprehend. For example, if you have a child in your group that has spent the last four years of her life watching cartoons, she many know an awful lot about Spongebob and his friends, but very little about actual sea life. As we are increasingly encouraging children to interact with and produce informational text, per the Common Core State Standards, we know that having a broader understanding of the world will help children be good consumers and producers of that kind of text. Here are some strategies that you can try right away as you work to build children’s world knowledge:

1) Plan to include an informational text read aloud in your day. My colleague Nell Duke found that very little time is spent in classrooms actually reading informational text with and to children (Duke, 1999). If we’re not exposing children to fact-based texts, their knowledge of the world will be constructed through stories and other input that may not be factually accurate (For example, in The Very Hungry Caterpillar, the caterpillar comes out of a cocoon and is a butterfly. This is factually incorrect; moths come out of cocoons and butterflies come out of a chrysalis.) There are some excellent wordless, low-level, and advanced informational texts available in both book and children’s magazine format.

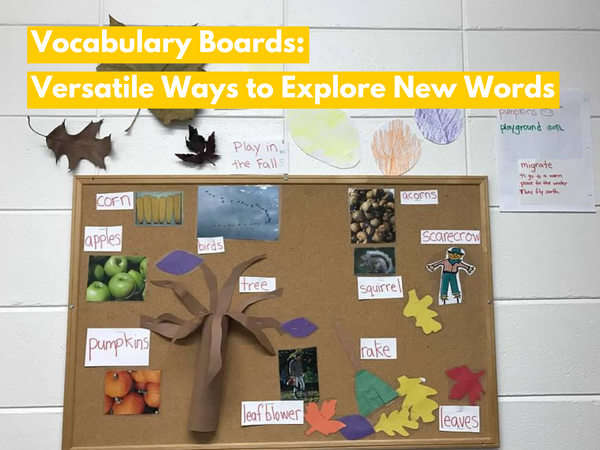

2) When reading informational text, take the time to talk about the vocabulary in the text. This will not only help your children understand this particular text, but it will give them information they can draw on in other readings and situations.

3) Include opportunities for children to freely interact with informational text in each activity center in your classroom (block area = books on construction, transportation, or homes; dress up area = theme related books such as cookbooks, books about the fire station, or taking care of pets; science corner = books on the materials present, such as books about birds if you have feathers on display, plant books with seeds to sort, etc.)

4)

Consider linking your informational text reading to a theme or project topic.

Theme-based teaching encourages children to make connections to topics within the theme (e.g., transportation includes cars, trucks and boats) but also across themes (people live in homes, and animals do too!). Think about how you are actively assisting children to make connections to content through your exposure to texts that discuss your topic.

5)

Design primary experiences for children to make sense of the learning themselves

.

(A primary experience is something that happens to you personally.) Children (and adults!) learn best when information is repeated, relevant to them, and real. Our brains move information from short-term memory to long-term memory (learning) when they get the message through multiple inputs (smell, touch, taste, excitement) that a thing is worth remembering. When we want children to learn about apples, we can read to them about how apples grow, read a story about making a pie, or we can talk about apples while children explore actual apples. By combining all three (informational text, story, and apple exploration), we increase the likelihood that children will retain what we’re talking about. If we link apples to something personal to them, like the time they made pie with Grandma, we can make the learning even more powerful.

Each of these strategies is a way to build world knowledge and lay a foundation for activating prior knowledge later. One more important strategy is to

honor what your children already know

. Every child knows about something. Make connections to their own interests and knowledge. My colleague with the student who had little knowledge of picnics got him to share a great deal about life in the city when they were talking about communities. Always start with the known and build to the new.

Each of these strategies is a way to build world knowledge and lay a foundation for activating prior knowledge later. One more important strategy is to

honor what your children already know

. Every child knows about something. Make connections to their own interests and knowledge. My colleague with the student who had little knowledge of picnics got him to share a great deal about life in the city when they were talking about communities. Always start with the known and build to the new.

So what happened with my failed read aloud? After muddling through, I encouraged the teacher to set up a dramatic-play grocery store so the children could act out grocery store play and talk about how stores work. The children that had been to actual grocery stores guided the children that hadn’t. The teacher put out a number of books about grocery stores, both fact-books and stories, and let the children make the content their own. My failure turned into a rich learning experience for that class and for me!

~~~

Susan Bennett-Armistead, PhD, is an associate professor of literacy education, the Correll Professor of Early Literacy, and the coordinator of literacy doctoral study at the University of Maine. Prior to doctoral study, Dr. Bennett-Armistead was a preschool teacher and administrator for 14 years in a variety of settings, including a brief but delightful stint in the Alaskan bush.

~~~

For more information on the My World series by this author, you can click here to visit the series page on our website or click the image below to download an information sheet. Other informational text books pictured in this article were from Zoozoo Animal World and Story World Real World .

![6 Fun and Easy Activities to Practice Sequencing [Grades K-1]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-5_bf1ae163-a998-4503-aa03-555b038d1b76_600x.png?v=1689961568)

![Leveraging Prior Knowledge Before Writing and Reading Practice [Grades 1–2]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-4_600x.png?v=1689961965)