This three-part blog series was previously published; we are re-sharing it to support teachers as they plan for guided reading groups, especially in a dual language setting.

Part 1: Book Selection –Find a "just right" book for your reading group

Part 2: Book Introduction –Prepare students before reading

Part 3: First Read –Support students with effective prompts and cues

By Carla Bauer-Gonzalez

I will focus on developing a practical book orientation in part two of this three-part blog series (catch up on part one here). I will share excerpts from actual Guided Reading Lessons and detailed examples.

" The introduction to the new book is particularly important for the child who does not have good control of language (for whatever reason) " (Clay, 2016).

A strong book orientation before reading is best practice for all readers and critical for Spanish Second Language Learners who may not be familiar with essential vocabulary and structures. We can assess students' knowledge of these items through the book introduction and teach and rehearse them if needed. As Clay states,

" The book orientation prepares the reader for a successful experience during the first reading. "

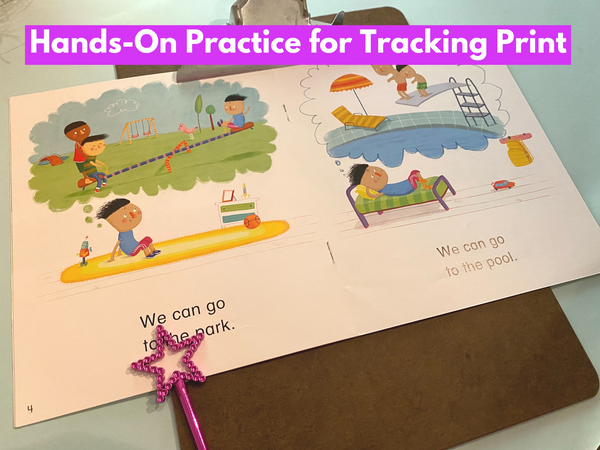

"Successful reading" is not exclusively about decoding elements like sound/symbol correspondences and syllable combining. Instead, "successful reading" is about how each student integrates decoding knowledge with what they know about the text's vocabulary and language structures.

In successful reading, decoded words conjure a mental image. For example " gran-ja," el lugar dónde viven muchos animales. If granja doesn't exist in the child's oral language, they may decode it perfectly, but with no thought of red barns and mooing cows. During the book orientation, we must identify the vocabulary and language structures the reader knows and fill in the gaps.

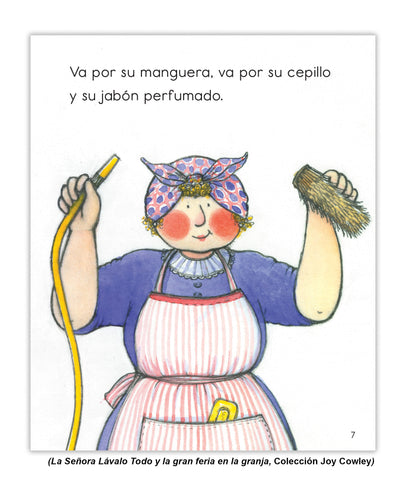

Following is a sampling of the nine teaching strategies I used during the book orientation for La señora Lávalo Todo y la gran feria en la granja .

1. Maintain a Conversational Tone: The book orientation should feel like a natural conversation (Clay, p. 115 ), with the children contributing as much as the teacher. To encourage this, start with an open-ended invitation to talk. If it's your goal for the conversation to be in Spanish, casually echo any child's English contribution with the Spanish equivalent. This validates his contribution, allows him to hear the Spanish, and promotes the feel of natural conversation.

Maestra (Teacher): ¿Quién cuenta lo que estará pasando aquí?

Aaron: She's talking.

Maestsra (Teacher): Está hablando con...

Lilly: ...con los animales

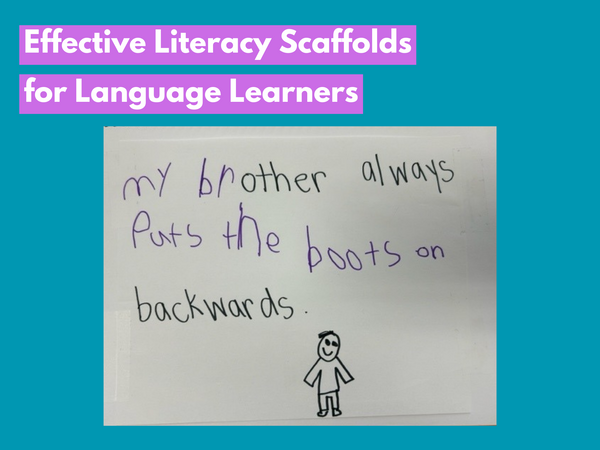

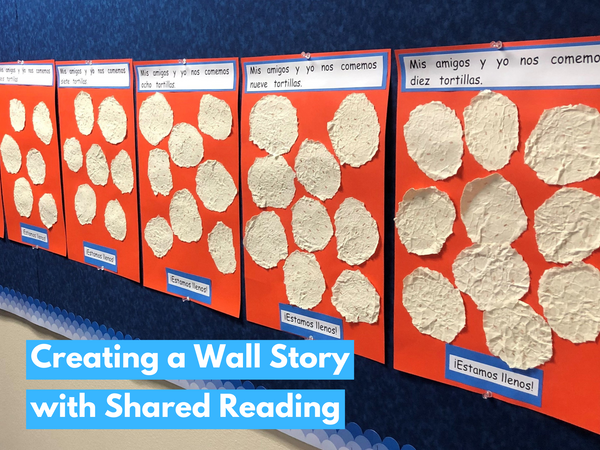

2. Temporarily Replace Text Words: I changed two words on the page below. The original text said, "'Estos animales son un desastre!' exclama la señora Lávalo Todo. 'Ay, que desgracia,' lamenta la señora Lávalo Todo." I used post-ti tape to temporarily substitute familiar words more likely to be in the students' lexicon. In the future, after having read the book a few more times, we will remove the post-it tape and learn about the author's use of these words.

3. Using CLOZE: The Merriam-Webster definition of CLOZE is a test of reading comprehension that asks the person being tested to supply words systematically deleted from a text.

While we aren't testing students during the book orientation, using CLOZE helps assess which concepts, vocabulary, and language structures the students already know. Use this technique at the word level to determine if a specific word is in the students' existing lexicon. Say the first syllable to see if this elicits the desired word from the students. If not, teach the word by saying it and asking students to repeat it.

4. Utilize Cognates: Cognates are words or morphemes related by derivation, borrowing, or descent. For example, "disaster" and "desastre" in English and Spanish. Pointing out such similarities between Spanish and English words helps children use what they already know in one language to solve unknown words in another. When reading, I anticipate that Aaron and Lilly will read, "Estos animales son un disaster." That is fine for now; it makes sense. We will reread this book many times, with plenty of opportunities to address this substitution.

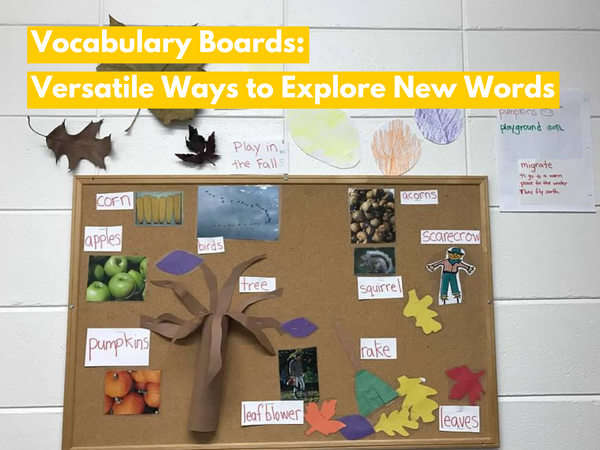

5. Embedded Word Work: Occasionally, incorporate word work by asking students to locate specific words in the text. Children use word parts across the whole word for efficient decoding at this level. They also use known words to decode unknown words. Traditionally, children are taught to break Spanish words into syllables. This is useful in the beginning stages of learning to read, but long term, we want children to see parts bigger than syllables as soon as possible. Practice finding small words inside larger words versus strictly syllable decoding.

6. Frontloading Synonyms: Sometimes, we might be afraid of "giving away too much" during the book introduction. Try using synonyms to establish meaning without giving away the exact text words, so you can rehearse essential vocabulary (' manguera' in this example) without giving away the whole structure.

8. Multimodal Engagement: I thought " Cepilla, cepilla y cepilla " was a strange structure that the students would be unlikely to anticipate. I decided to plant it directly and rehearse it with pantomime during the orientation. Adding movement allows students to access text through visual, auditory, and kinesthetic modalities.

9. Time Management: A thoughtful and well-orchestrated book orientation is time well-spent. Remember that every page will not contain vocabulary and structures that require immediate attention. We rarely need to do everything shared here during one book introduction. If time is an issue, consider teaching the book over two days: do the book orientation one day and read the next. Clay describes this adaptation to the customary one-day teaching of a new text by saying,

" This additional support may be necessary for a child who knows little about stories and storytelling, or who is an English language learner, or who for some other reason has limited experience with the language of books " (p. 116).

In the next part of this series, I will discuss how I approach the first reading of this book with my dual language learners.

Spanish Guided Reading Level Sets offer all of the Spanish leveled readers we currently have available at each guided reading level, intervention (Reading Recovery) level, or DRA level. Add a just-right level range of Spanish books to your bilingual or dual-language classroom library . Guided reading levels A–M.

~~~