This guest post by Susan Bennett-Armistead, author of our

My World informational texts

, is part of an ongoing series in which she discusses informational text and its benefits and uses. Check back regularly to catch her next post!

This guest post by Susan Bennett-Armistead, author of our

My World informational texts

, is part of an ongoing series in which she discusses informational text and its benefits and uses. Check back regularly to catch her next post!

“How do you decide what to teach?”

Because I have the privilege of visiting many programs around the country and the opportunity to meet with many skilled teachers, I get asked that question a lot.

One of the wonderful things about teaching in preprimary classrooms is we often have more freedom to select our topics of study than our friends in K–12 education do.

At the same time, that can be a bit daunting. Coming up with units of study, whether you’re following the children’s lead with a Reggio Emilia approach or working from a theme-based perspective, means that you need to think carefully about several important things:

1) Know your learners .

This may seem obvious, but

you need to be very aware of what your children know and can do as well as knowing what gaps they may have in knowledge

. The whole idea of assessment-led instruction has often been misunderstood to mean that we have to formally assess children’s knowledge before we can instruct them. As you know, many schools spend entire weeks assessing children’s knowledge. That’s not the only, or even the best, way to gain an understanding about what children know. Through informal assessments such as visiting with children, observing their play, and investigating their interests, you can gain a great deal of information about what children know. Simply playing games such as Candyland with them can tell you who knows the names of the colors and who does not. Developing a record keeping system, such as an anecdotal record log that you peruse from time to time can help you decide what content you should be building on.

2)

Move from the known to the new

.

2)

Move from the known to the new

.

Children (and adults) learn best when information is repeated, relevant to them, and real.

One of the best ways to make learning relevant to children is to link it to something they already know about.

For example, I used to teach in the Alaskan bush for a couple of years. The way most of us got around was by small planes. There were no children in my group who had not been on an airplane. If I was doing a unit on transportation and decided to set up a vehicle in my dress up area, it would have to be a plane or a boat since that’s what the children were most familiar with. I now live in rural Maine. Very few children here have flown in planes. A unit on transportation here would not start off with an airplane in the dress-up area; it might have a school bus instead. I could eventually turn my school bus into an airplane, but I’d need to bridge it for my children to help them understand that planes and buses have some similarities, as well as important differences.

3) Start with the child .

When I was teaching preschool, like many teachers, I started with the same themes each year. Using the principle above, I moved from what the children knew best—themselves—and gradually expanded their world. Here are some examples of my themes, in chronological order:

- Marvelous Me

- My Family

- Friends at School (about making friends and the community of school)

- My Neighborhood

- Community Heroes

- Healthy Humans

- Sensing the World Around Us (a two-week unit on senses)

- Trees (living in the north, we needed to talk about changes in the trees)

- Feelings (usually timed for Halloween so we could talk about things that scare us)

By this point in the year, I knew children’s interests and issues well so I could start building themes built on their content knowledge and passions. Additional themes have included:

By this point in the year, I knew children’s interests and issues well so I could start building themes built on their content knowledge and passions. Additional themes have included:

- Under the Sea

- Dinosaurs

- Animals in Winter

- Rocks and Minerals

- Mammals

- Amphibians

- Insects

- Birds All Around Us

- Everything Grows

- Art and Artists

- Planes, Trains, and Automobiles

- Once Upon a Time (genre study of fairytales)

- Friends Forever (focusing on promoting social problem-solving)

- Life in the Forest

- Life in the Desert

- Space

- Change (addressing the changes expected with the end of school and children's moving on)

By approaching my year in this way, I started with the child and ended as far from the child as possible (in space!), which helped their world and their knowledge to grow over time.

4) Designing the Content-rich Classroom.

You may have noticed that none of my themes were the letter or color of the week, nor is there anything on this list about teddy bears. Theme selection has to be rich enough that the children can learn about something for a week or more; I generally did units for about 2 weeks. There have to be facts to learn, literature to link the facts to, and enough age-appropriate content for children to sink their teeth into. Science- or social-studies–focused themes tend to offer more depth to talk about than doing a unit on, say, The Gingerbread Man . To plan this way, you have to first decide:

a. What are the facts I want children to know about this topic?

b. What do children already know about this topic?

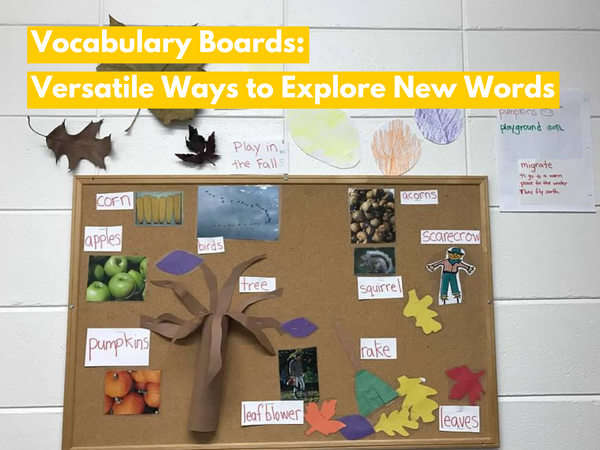

c. What vocabulary should children gain to master this topic?

d. What experiences can I provide for children to gain this knowledge?

The

My World series

is theme-based, and the teacher’s guide, available

here

, offers some examples of theme planning for the five themes in the series. Additional resources you might try are

Teaching Young Children Using Themes

and

Themes Teachers Use,

both by Kostelnik et al.

The

My World series

is theme-based, and the teacher’s guide, available

here

, offers some examples of theme planning for the five themes in the series. Additional resources you might try are

Teaching Young Children Using Themes

and

Themes Teachers Use,

both by Kostelnik et al.

After generating the answers to the questions, planning for all areas of development falls into place using whatever planning format you’ve been using. The trick though, is that as the teacher, you have to ask the most important questions of all:

What do

I

need to know about this topic to effectively teach it? What resources do I need to investigate to make sure my content knowledge is accurate?

My greatest fear is teaching misinformation out of my own ignorance! I once sat in on a class where the teacher told the children that the moon was the closest planet to the earth. To make sure I don’t do something like that, I often read up on a topic using informational children’s books to make sure my content knowledge is accurate and up to date, as well as framed in a way that young children can understand it.

As mentioned in previous posts, building children’s knowledge of their world benefits them now, as they’re developing their own understandings of the world around them, but also later when they’re trying to make sense of material they’re reading about . Planning your classroom and your year around building that knowledge can enrich them with a lifetime of curiosity and learning.

~~~

Susan Bennett-Armistead, PhD, is an associate professor of literacy education, the Correll Professor of Early Literacy, and the coordinator of literacy doctoral study at the University of Maine. Prior to doctoral study, Dr. Bennett-Armistead was a preschool teacher and administrator for 14 years in a variety of settings, including a brief but delightful stint in the Alaskan bush.

~~~

For more information on the My World series by this author, you can click here to visit the series page on our website or click the image below to download an information sheet.

![6 Fun and Easy Activities to Practice Sequencing [Grades K-1]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-5_bf1ae163-a998-4503-aa03-555b038d1b76_600x.png?v=1689961568)

![Leveraging Prior Knowledge Before Writing and Reading Practice [Grades 1–2]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-4_600x.png?v=1689961965)