by Beth Richards, Literacy Interventionist, Reading Recovery Teacher

Kids love telling stories. As teachers, we’ve heard endless recounts and retells. Even tattling is a way to tell a story! But exactly how do students decide which details to include and which ones to leave out? And how can we enhance that decision making and transfer it to summarizing nonfiction texts?

Fountas and Pinnell (2009) define summarizing as putting together and remembering important information “while disregarding irrelevant information during or after reading.” Students have to learn to discern and label what’s most important from supporting details. Students must be given appropriately leveled texts; if you provide support, texts at instructional levels can be used, but without support, the texts need to be at the students’ independent levels. Please keep in mind that students often need to access nonfiction texts at a level or two lower than their fiction levels due to concepts and vocabulary. The following sections contain beneficial concepts and strategies for supporting students as they learn to summarize.

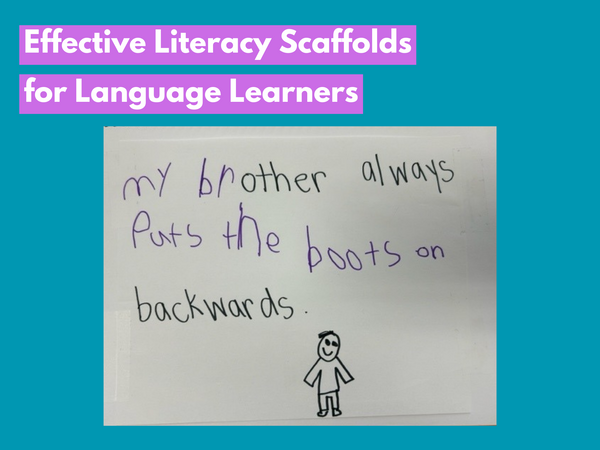

Language Development

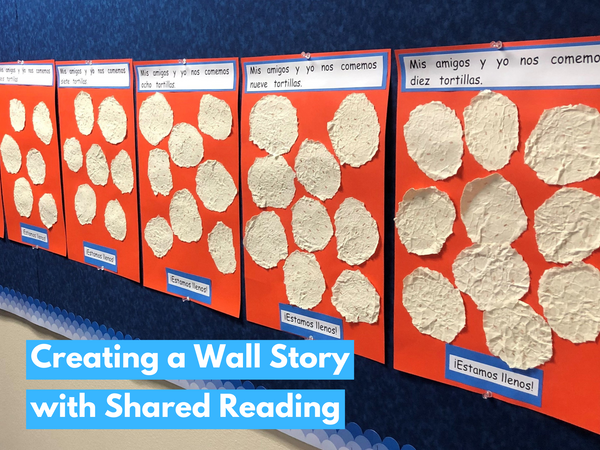

Marie Clay reminds us that “the child’s ultimate resource for learning to read and write is spoken language; all his new learning becomes linked in his brain with what he has already learned about the language he speaks” (2016, 24). So one of the first ways we can support students’ abilities to summarize is through language. Provide plenty of opportunities for students to practice through storytelling and retelling. This can be done through a shared classroom experience. Involving children in “the retelling of an event using language that includes setting, characters, events, and an ending is an important precursor to comprehension” (Dorn & Soffos, 2005). Although many of these shared classroom experiences will allow for a more descriptive retelling, the classroom experience can be informational in nature as well, such as investigating the life cycle of a butterfly or one of the other animals represented in Hameray's Zoozoo Animal World series, there are plenty to choose from! “The more effectively they can use oral language, the more knowledge they can bring to becoming literate. And there is only one way to develop oral language—through meaningful interactions with others” (Fountas & Pinnell, 2009).

Exposure to Nonfiction Texts

Investigate your classroom library or book room. What percentage of texts are nonfiction? The number of narrative texts made available to students typically outweighs informational genres, and children’s reading selections reflect this availability (Donovan et al., 2000). In an article from Norrie Eure and Nancy Anderson (2007), teachers are encouraged to provide students with access to nonfiction texts by reminding us that some students prefer nonfiction texts and use them as a springboard literacy development. In addition, as children progress through the grades, there is an increased expectation to read and write nonfiction. By being more conscious of the texts we use to model, share, and provide for students, we can familiarize them with the layout of nonfiction texts and lay a more solid foundation for their ability to summarize.

Demonstration and Modeling through Think-Alouds

“Think-alouds are a way of modeling or “making public” the thinking that goes on inside your head as you read” (Cunningham & Allington, 2009). Put yourself in a child’s shoes. When adults read aloud, they often read fluently and accurately. There are rarely moments of monitoring and self-correcting. Kids know that is the end result, but how do they get there? As teachers, we need to fill in the gaps for students and teach them the why and how, so they can become strategic, fluent readers with strong comprehension. Think alouds are an excellent platform for this. It is imperative that your think-aloud does not just show or address the correct way but explains why and how you are making these decisions to lead you to the result—a summary. As you read and share a nonfiction text with students, stop along the way and talk out loud, saying things like, “The most important thing I’ve learned so far is…” or “I bet this is important because…” Your language will become the students’ inner language as they head into their texts.

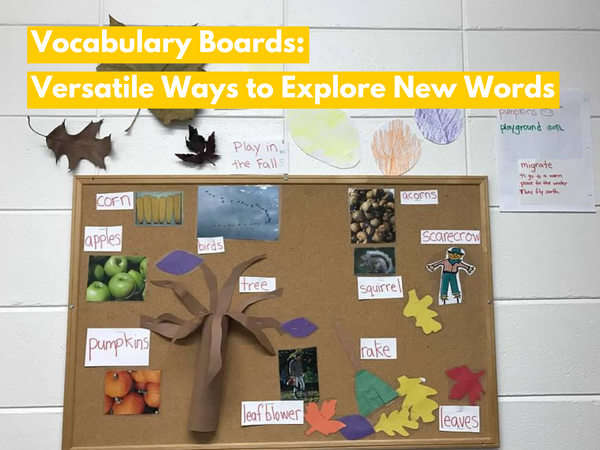

Teaching about Text Features

Authors and publishers use specific features to assist students with summarizing nonfiction. These may include headings, subtitles, graphs, charts, glossaries, indices, timelines, photos, captions, etc. These text features are often a built-in scaffold that can help students understand main ideas and details, improving their ability to summarize. Teach students how to use and navigate these text features.

Let’s look at an example using Hameray’s Usain Bolt: "My Name is Bolt. Lightening Bolt , " from their Inspire! series. Students can read the chapter titles in this text to infer and note what the chapter will be about. That will help them decide which details from the chapter relate to the title and may be essential to include in a summary. In addition, the text also features a timeline of Bolt’s life, which can provide a framework for providing an oral or written summary of his life. Students can also access the glossary to help clarify and understand the vocabulary words used throughout the text. Understanding how to use these text features and supports will improve students’ abilities to summarize nonfiction texts.

Setting students up with appropriately leveled texts, allowing opportunities for oral language retellings and summaries, providing exposure to nonfiction texts starting early on, teaching about text features, and using think-alouds will set students up to be successful summarizers of nonfiction texts. For more ideas on improving students’ literacy development, continue to revisit this blog frequently!

~~~

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.

![How to Improve Summarizing with Nonfiction Books [2-3]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post_5_a4d0d4ad-5c85-4745-b614-151209db9ab6_1024x1024.png?v=1689961577)