By Dr. Susan Bennett-Armistead, Professor of Literacy Education, Guest Blogger

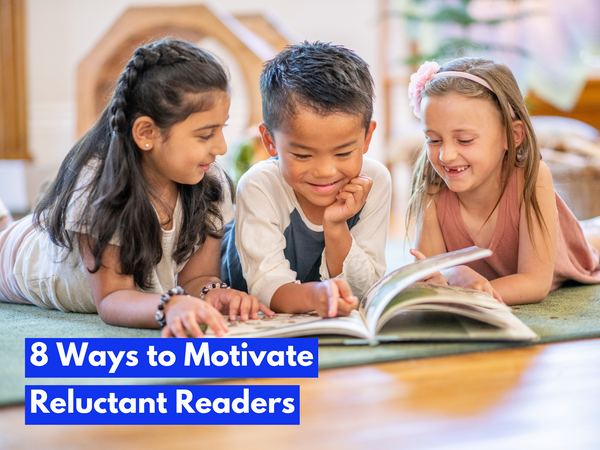

“I’m going to kindergarten! I’m going to learn to read!” my daughter's five-year-old friend announced to me at her kindergarten orientation night a few weeks ago. While many kindergartners want to read, there are some kids who need a significant amount of support to develop foundational skills before they can dive into the complicated process of reading with fluency. This can be tricky especially if you're trying to build content-area literacy! Keep reading because I'll share tips to weave informational texts into classroom activities to pique children’s love of reading beyond a guided reading lesson.

Have you ever tried a topical book club? Select a theme that you’d like to teach students about, such as winter animals or transportation. Collect a range of leveled books on this theme for children to read. Be sure to include wordless books on the topic as well. Create small study groups that consist of struggling readers and students who can read independently, and provide each student with appropriately leveled texts. This allows for each child to learn from a book at his or her own level and pace while contributing to the group.

Have you ever tried a topical book club? Select a theme that you’d like to teach students about, such as winter animals or transportation. Collect a range of leveled books on this theme for children to read. Be sure to include wordless books on the topic as well. Create small study groups that consist of struggling readers and students who can read independently, and provide each student with appropriately leveled texts. This allows for each child to learn from a book at his or her own level and pace while contributing to the group.

Invite children to explore the texts and generate a fact that's relevant to the theme you selected for the book club. Encourage the kids who opt for a wordless book to study each page's image to discover a fact. You should also excite the students who select leveled readers to find an interesting fact in their books. Have them write their facts on a piece of paper. Early in the year, you might need to use dictation to write their sentences on the board. You can try having students illustrate their facts, too.

Be sure to ask them where they got the facts that they report. Whether kids are using wordless books or a text with a simple sentence structure, have them show you their sources. Clarifying this information, and consistently using language from a source, will help children to start thinking critically about sources and facts.

Have you ever linked a lesson to the internet? Let's say for your next kindergarten science investigation, you're going to study ocean life. Using level A books, such as

My World’s

Animals in the Sea

or

Go Fish!

, invite children to select one animal in the book. You can pair a kindergartner with an older student volunteer to find out three things about their animals using a kid-friendly internet search engine, such as SafeSearchKids.com. If there aren't enough volunteers, you can make small groups for each volunteer.

Have you ever linked a lesson to the internet? Let's say for your next kindergarten science investigation, you're going to study ocean life. Using level A books, such as

My World’s

Animals in the Sea

or

Go Fish!

, invite children to select one animal in the book. You can pair a kindergartner with an older student volunteer to find out three things about their animals using a kid-friendly internet search engine, such as SafeSearchKids.com. If there aren't enough volunteers, you can make small groups for each volunteer.

You can decide which three questions will be used for everyone's investigation by getting students' feedback before starting. Here are some examples of questions to use:

What kind of animal is this? What does my animal eat? How big is my animal? Does anything eat my animal?

If you'd like to give students a template to record the information they find, you should create a sheet with the class questions already typed on it. Be sure to include room for writing and space for an illustration.

You can decide which three questions will be used for everyone's investigation by getting students' feedback before starting. Here are some examples of questions to use:

What kind of animal is this? What does my animal eat? How big is my animal? Does anything eat my animal?

If you'd like to give students a template to record the information they find, you should create a sheet with the class questions already typed on it. Be sure to include room for writing and space for an illustration.

After every student has completed his or her sheet of animals facts and artwork, collect all the pages and use them to create a class animal book on the topic. I like to rotate class-made books among students' families to take home and read. This is a great way to boost family literacy because parents and relatives love to read aloud. This also helps your families better understand what their kids are learning at school. Often, this will prompt more families to want be more active in facilitating learning at home, which will have a great impact on tapping into the curiosity of your students.

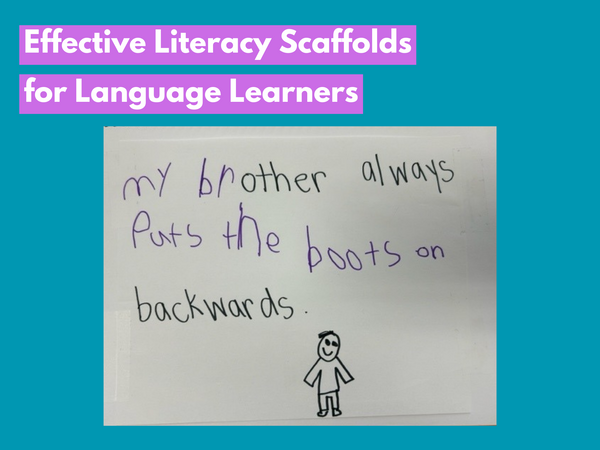

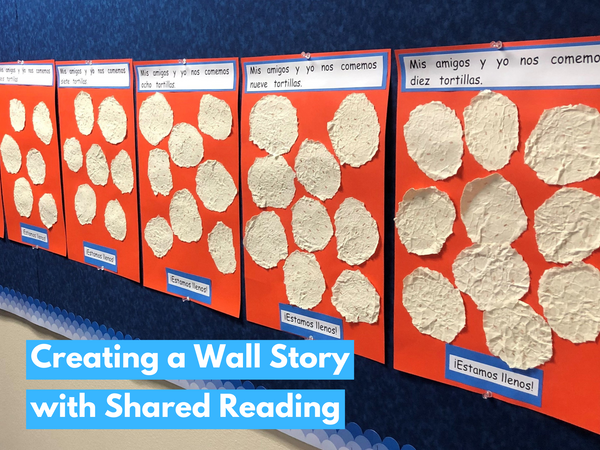

Have you ever transformed a wordless book? To do this, select a wordless book from your leveled classroom library. Share the book with students and ask them to come up with words that should be on each page. For example, if you were to use the book

Pets

, provide a sentence stem, such as "Some pets are . . . " and encourage kids to help you complete the sentence.

Have you ever transformed a wordless book? To do this, select a wordless book from your leveled classroom library. Share the book with students and ask them to come up with words that should be on each page. For example, if you were to use the book

Pets

, provide a sentence stem, such as "Some pets are . . . " and encourage kids to help you complete the sentence.

As you take dictation from students, write their words on sticky notes. Next, invite the child to place the sticky notes in the correct location on the page. Have the child read the book to you or to a partner a couple of times. Then you can rearrange the sticky notes and have them try reading again. This is another good idea to use as a take-home activity for students and their families to improve vocabulary.

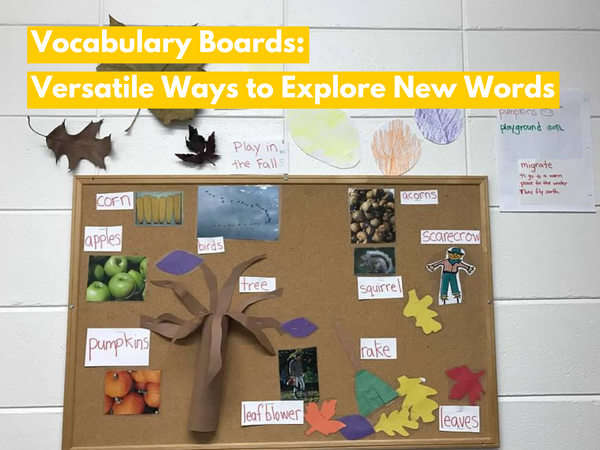

Are you optimizing your resource library to enhance the experience in each of your classroom centers? The centers around your classroom should each have their respective manipulatives: houses could go in your block area, insects could be placed near an aquarium for the class turtle in the science center, etc. Each center, as well as other areas of your classroom, will benefit from having relevant informational books nearby for children to access.

Are you optimizing your resource library to enhance the experience in each of your classroom centers? The centers around your classroom should each have their respective manipulatives: houses could go in your block area, insects could be placed near an aquarium for the class turtle in the science center, etc. Each center, as well as other areas of your classroom, will benefit from having relevant informational books nearby for children to access.

It's important to remember to include reading material that may be above and below students' reading levels. You might also want to find children's magazines to help reinforce print concepts, such as ZooBooks. By putting a variety of leveled texts in your classroom centers, you'll spark a love of reading independently and provide a solid foundation for content-area instruction.

We need to promote curiosity, independence, content-area literacy about the world around our students, but most of all, we need to send the message to early learners that there are many interesting things to read in books. You can progressively help students see that their questions can be answered with the help of books by placing a range of nonfiction and fiction books for kids around your classroom. Whether you incorporate the books in a guided reading lesson or draw upon them throughout the day, your key to building content-area literacy and curiosity is asking, “Is there a book that will help find the answer?”

Be sure to continue checking back with us for more helpful tips to build important reading skills!

Susan Bennett-Armistead, PhD, is an associate professor of literacy education, the Correll Professor of Early Literacy, and the coordinator of literacy doctoral study at the University of Maine. Prior to doctoral study, Dr. Bennett-Armistead was a preschool teacher and administrator for fourteen years in a variety of settings, including a brief but delightful stint in the Alaskan bush. She is also the author of our

My World Collection

and several books in our

Kaleidoscope Collection

. If you like what you read here, be sure to read more

helpful articles by Dr. Bennett-Armistead on our blog

.

Susan Bennett-Armistead, PhD, is an associate professor of literacy education, the Correll Professor of Early Literacy, and the coordinator of literacy doctoral study at the University of Maine. Prior to doctoral study, Dr. Bennett-Armistead was a preschool teacher and administrator for fourteen years in a variety of settings, including a brief but delightful stint in the Alaskan bush. She is also the author of our

My World Collection

and several books in our

Kaleidoscope Collection

. If you like what you read here, be sure to read more

helpful articles by Dr. Bennett-Armistead on our blog

.

![6 Fun and Easy Activities to Practice Sequencing [Grades K-1]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-5_bf1ae163-a998-4503-aa03-555b038d1b76_600x.png?v=1689961568)

![Leveraging Prior Knowledge Before Writing and Reading Practice [Grades 1–2]](http://www.hameraypublishing.com/cdn/shop/articles/Red_Typographic_Announcement_Twitter_Post-4_600x.png?v=1689961965)