By Beth Richards, Literacy Interventionist, Reading Recovery Teacher, Guest Blogger

Today's blog post is the second in a two-part series written to help you decide on the most important moves you can make when teaching students who are reading at levels A–C. If you missed the first part, you can read Making Thoughtful Decisions at Guided Reading Levels A–C, Part 1 .

Locating Visual Information to Find Something Familiar

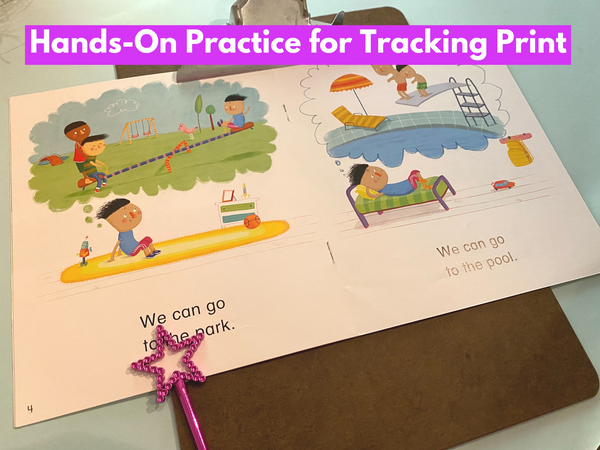

Clay tells us, “For the beginning reader not much is recognizable among the squiggles, lines, and dots. There may be only a few letters or features that the child can recognize. He does not have many visual signposts to guide him. Locating the visual information that he can recognize is a skill he will learn” (2005, 21). For most of our students, this will be the very first act of searching for visual information. It’s imperative it starts now in order to develop and become more efficient over time.

Clay tells us, “For the beginning reader not much is recognizable among the squiggles, lines, and dots. There may be only a few letters or features that the child can recognize. He does not have many visual signposts to guide him. Locating the visual information that he can recognize is a skill he will learn” (2005, 21). For most of our students, this will be the very first act of searching for visual information. It’s imperative it starts now in order to develop and become more efficient over time.

If you notice that a child is not recognizing a word that is known or partially known in the text while reading, capitalize on this opportunity. You can stop them at the end of the sentence, praise their meaningful attempt, but tell them to look closely and try again because there’s something they know on this page. If they are unable to locate it, increase your support by asking them to find the word.

After locating, encourage students to look closely and use that word to help them in their reading. Remind them that in every instance, when they see that word, they need to say it. In subsequent texts, encourage the child to locate something known on the page prior to reading.

Noticing Voice and Print Mismatch

This is the beginning of monitoring, a behavior that is crucial for struggling and striving readers. In text levels A–C, many children begin to notice with known words. Their mouths can move ahead of their eyes, but when they see a word they know in print, they stop because they know their mouths didn’t just say it. It’s a signal that something is wrong and needs fixing. Praise this monitoring and encourage the child to try again.

Another opportunity for developing monitoring behaviors is to encourage the child to start cross-checking. This means to check their oral prediction against the visual information on the page (usually the first letter of a word at this stage). For example, if a child predicts

bunny

, but the text says

rabbit

, praise his meaning-making and ask the child to check and see if it looks right too.

Another opportunity for developing monitoring behaviors is to encourage the child to start cross-checking. This means to check their oral prediction against the visual information on the page (usually the first letter of a word at this stage). For example, if a child predicts

bunny

, but the text says

rabbit

, praise his meaning-making and ask the child to check and see if it looks right too.

To do this, put your finger under the first letter of the word rabbit and ask the child to check. Does the child see /b/ for bunny ? If not, ask the child what is on the page. Can the child think of what else may make sense and look like that? This may require additional support at first by modeling the following thought process: Bunny makes sense. Now let’s check to see if it says bunny or rabbit?

Direct their eyes to that first letter so they learn where to look to check for themselves. And encourage the checking even when their word prediction is correct to help train the eye and develop the habit of checking. Otherwise, your prompt becomes a signal that they are wrong, and they may not do the checking independently.

Conventions in Text

A child may not be able to read a known word once they are able to read and write independently. When thinking about that word and how it looks in text, it's important to ask yourself the following questions: Are they confused because they are used to seeing the word begin with a lowercase letter? Is the known word used in a new structure that is unfamiliar to them?

Often times, in questions (such as

Is the dog in here?

) students are not anticipating

is

to appear at the beginning of a sentence. They may also not be used to seeing

is

begin with a capital letter. A quick demonstration of writing the known word in its familiar form while saying,

You know a word like that

, helps students expand their understanding of that word, its visual form, and how it can be used.

Often times, in questions (such as

Is the dog in here?

) students are not anticipating

is

to appear at the beginning of a sentence. They may also not be used to seeing

is

begin with a capital letter. A quick demonstration of writing the known word in its familiar form while saying,

You know a word like that

, helps students expand their understanding of that word, its visual form, and how it can be used.

I used to get preoccupied with a child knowing every word on a page, and refusing to use texts that had unknown words. But that wasn’t helping my students become strategic readers. It’s not just about the words and accuracy at this stage of the game; it’s about developing the behaviors mentioned above. I had to learn to help children establish the pattern, and even help out when reading and to instead watch how they worked out the important things: directionality, one-to-one match, locating, and monitoring.

Keep in mind that reading is a “message-getting, problem-solving activity that increases in power and flexibility the more it is practiced” (Clay 1991, 6). You do not want to keep kids in level A and B texts for too long. Once their directionality and one-to-one matching is secure, move them into level C texts because we don’t want children to believe that reading is patterned. Also, at level C, we start to see more of a development with a story, which is crucial for teaching kids how to read in order to understand.

For guidance on how to make thoughtful teaching decisions in the moment for readers using level D–F texts, continue visiting our blog for the ideas to use with kids with these guided reading levels.

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.

Beth has been teaching for seventeen years. She has taught kindergarten, third, and fourth grades in Wisconsin. For the last six years, she has been a literacy interventionist and Reading Recovery teacher and loves spending her days helping her students develop and share her love of reading.